Résultats de l’étude:

« Evaluation d’un ensemble cohérent d’outils de repérage des troubles précoces de la communication pouvant présager un trouble grave du développement de type autistique » – 2005 / 2011 / 2017

Les résultats de l’étude sont parus en Décembre 2017 dans la revue Plos One sous le titre : « Infant and dyadic assessment in early community-based screening for autism spectrum disorder with the PREAUT grid » par Bertrand Olliac, Graciela Crespin, Marie-Christine Laznik, Oussama Cherif Idrissi El Ganouni, Jean-Louis Sarradet, Colette Bauby, Anne-Marie Dandres, Emeline Ruiz, Claude Bursztejn, Jean Xavier, Bruno Falissard, Nicolas Bodeau, David Cohen, Catherine Saint-Georges.

Nous mettons à votre disposition, ci-après, de manière résumée mais fidèle, les résultats de la recherche sur le signe PREAUT.

Vous pouvez également consulter l’article original (en anglais), la traduction de l’article en Français (exclusivité PREAUT), la présentation détaillée du signe PREAUT et la grille utilisée dans l’étude.

Historique de la démarche

En 1998, un groupe de psychiatres, psychologues et psychanalystes, tous praticiens de l’autisme, a fondé l’Association PREAUT, afin de réaliser une recherche visant la validation de signes de troubles de la communication pouvant présager un trouble grave du développement de type autistique.

La recherche PREAUT a été promue par l’Association PREAUT (Paris, France), représentée par son Président, Dr Jean-Louis Sarradet, et par le Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique (PHRC) du CHRU de Strasbourg, représenté par le Pr Claude Bursztejn.

La recherche PREAUT s’est adressée aux pédiatres et médecins de la petite enfance qui reçoivent les bébés dès la naissance pour les visites systématiques du protocole de santé publique français, dans le cadre de la PMI (Protection Maternelle et Infantile). A partir de 1999, Graciela C. Crespin et l’équipe PREAUT ont formé environ 600 médecins dans 12 départements de France métropolitaine et d’outre-mer à l’identification des signes de risque qui faisaient l’objet de la recherche.

Sans privilégier aucune étiologie, l’hypothèse PREAUT postule que les bébés qui risquent de développer un TSA pourraient présenter un déficit du besoin inné d’échanger et d’être une source de plaisir pour la personne avec laquelle ils interagissent, contrairement aux nourrissons en bonne santé.

Ces situations devraient pouvoir être observées dans la relation entre le bébé et son autre familier (habituellement, ses parents), bien avant que les marqueurs cognitifs habituellement recherchés –le pointage proto-déclaratif et le jeu de faire semblant du CHAT, par exemple – deviennent observables au cours de la deuxième année de la vie.

Contexte de la Recherche

Le contexte

Actuellement, les troubles du spectre autistique (TSA) regroupent un groupe hétérogène de troubles neurodéveloppementaux qui se caractérisent par des perturbations des relations sociales et de la communication, des comportements répétitifs et d’intérêts restreints, avec plusieurs degrés de gravité.

Bien que les études épidémiologiques des dernières années aient reporté une augmentation récente de la prévalence dans la population générale, ces résultats restent controversés, car en effet, l’augmentation pourrait être attribuée à des facteurs tels qu’une meilleure sensibilisation à la reconnaissance de la maladie, l’élargissement des critères diagnostiques ou encore le développement de services spécialisés susceptibles de les accueillir.

En 2010, la prévalence globale des TSA chez les enfants de huit ans était de 14,7 pour 1 000 aux États-Unis, soit un enfant sur 68, alors qu’en France, l’étude la plus récente, fondée sur le registre des handicaps (MDPH), fait état d’un taux de prévalence des TSA de 35/10 000 chez les enfants du même groupe d’âge, soit 3,5 enfants pour 1000.

La question du dépistage

Dans les dernières années, il y a eu un consensus autour de l’idée que les enfants atteints de TSA doivent être pris en charge le plus précocement possible.

Les objectifs de ces interventions précoces sont d’améliorer la communication et la socialisation, diminuer les comportements inadaptés et la détresse de l’enfant, et globalement, d’améliorer sa qualité de vie ainsi que celle de sa famille.

L’idée que le traitement très précoce chez les nourrissons pourrait infléchir la trajectoire développementale avant l’installation du syndrome autistique complet, voire prévenir l’autisme est de plus en plus admise, depuis que des études récentes ont évalué les bénéfices d’une intervention très précoce auprès des parents et des nourrissons à risque d’autisme, avec des résultats encourageants.

Ainsi, la mise en place d’un traitement précoce nécessite le développement d’outils permettant la détection des enfants à risque le plus tôt possible.

Cependant, l’âge minimum pour un diagnostic précoce fiable des TSA pose plusieurs questions scientifiques, ce qui fait que bien que les symptômes de TSA soient souvent présents tôt dans la vie, le diagnostic de TSA est encore actuellement fait entre trois et cinq ans.

Il y a au moins cinq facteurs qui peuvent nous aider à expliquer cette situation :

1) l’inquiétude parentale n’est toujours pas suffisamment prise en compte ;

2) l’installation d’un TSA se produit parfois après la deuxième année de la vie ;

3) les compétences développementales des bébés sont encore immatures pour répondre aux critères de diagnostic ;

4) les diagnostics différentiels sont complexes à un âge précoce (particulièrement en cas de déficience intellectuelle, DI) ;

5) et enfin, le diagnostic est risqué avant l’âge de deux ans car il est plus susceptible d’être instable.

Les critères de diagnostic des TSA ont changé ces dernières années

On considère aussi que le système de classification actuel peut contribuer à l’instabilité croissante de l’attribution du diagnostic de TSA.

En effet, le diagnostic initial pourrait évoluer vers une récupération spontanée ou un retard de développement sans traits autistiques.

Par ailleurs, la détection précoce ne peut être détachée de toute interférence avec le résultat, car les enfants détectés sont plus susceptibles d’être rapidement pris en charge, en particulier si l’on tient compte du fait qu’il est admis qu’une intervention précoce pourrait diminuer les symptômes autistiques et améliorer le pronostic développemental pour une proportion significative d’enfants.

Les études sur les outils de dépistage

Depuis que Baron-Cohen a testé la CHAT (Checklist for Autism in Toddlers) sur des enfants de 18 mois, de nombreuses études ont tenté de développer et tester des outils de dépistage.

Ces études ont le plus souvent ciblé des nourrissons à risque (par exemple, des enfants évalués pour suspicion d’autisme, des fratries d’autiste, ou des bébés atteints de maladies génétiques) ou encore sur des enfants qui ont déjà reçu un diagnostic de TSA.

Les études en population générale doivent dépister un très grand échantillon pour obtenir suffisamment d’enfants positifs, ce qui les a rendues moins fréquentes.

Ainsi, l’ensemble de ces études connaissent beaucoup de limites méthodologiques, et au-delà de la valeur de l’outil testé, le dépistage précoce est confronté au problème de la stabilité incertaine des TSA avant l’âge de deux ans.

Au cours de la deuxième année de vie, les outils de dépistage précoce les plus utilisés comprennent l’échelle CHAT, ou une version modifiée de la CHAT, notamment la M-CHAT (Modified-CHAT), et la Q-CHAT (Quantitative-CHAT) ; d’autres outils ont été testés avec des résultats variables.

La CHAT s’est avérée avoir une bonne spécificité, mais une faible sensibilité ; la M-CHAT a montré une meilleure sensibilité, mais produit de nombreux faux positifs.

Plus récemment, une nouvelle procédure M-CHAT en deux étapes, avec un entretien de suivi, a montré des valeurs métriques potentiellement intéressantes sur un échantillon à faible risque. Les chercheurs poursuivent actuellement leurs efforts pour dépister l’autisme à un très jeune âge.

Dès l’âge de 12 mois, peu d’outils ont été testés prospectivement. Deux outils ont été testés sur des fratries à risque, et trois ont été évalués en population tout-venant.

Avant 12 mois, seuls trois outils ont été testés prospectivement et ont montré qu’ils avaient une valeur prédictive : la CSBS-DP DP IT a été utilisée pour dépister en population générale les nourrissons de 6 à 8 mois et de 9 à 11 mois et la TBCS (Taiwan Birth Cohort Study) a été utilisée pour dépister des nourrissons de 6 mois en population générale. Ces deux outils ont montré une valeur prédictive positive (VPP) faible.

Le troisième outil est la grille PREAUT (Programme de Recherches et d’Études sur l’Autisme), utilisée pour dépister très tôt des nourrissons à risque, et qui fait l’objet de la présente étude.

De l’observation du comportement du nourrisson à l’observation des interactions

Plusieurs auteurs ont proposé que le dépistage précoce des TSA devrait s’appuyer sur les interactions dyadiques, plutôt que sur le comportement des nourrissons. En effet, les retards dans les étapes de développement ou les difficultés dans les interactions sociales précoces ne sont pas suffisantes pour prédire un TSA avant un an.

La conception des troubles autistiques comme « des cascades développementales » suggère que le dysfonctionnement d’un système peut influencer un autre système au fil du temps et ainsi organiser une trajectoire développementale déviante. Des études récentes sur les TSA, utilisant une approche rétrospective à travers des films familiaux ou une approche prospective sur des échantillons à risque (p. ex., fratries, plaident en faveur de ce changement par l’étude de la qualité des interactions précoces (à travers la synchronie, la réciprocité et l’engagement émotionnel).

En effet, les mères de nourrissons à risque tentent de compenser le manque d’interactivité de leur enfant en intensifiant la stimulation dans les échanges dès le début de la vie. Green a proposé l’idée que les spécificités interactives des nourrissons à risque d’autisme peuvent modifier les comportements parentaux dans des boucles interactives, et Crespin propose la même idée dans son concept des « états de sidération ».

C’est pourquoi il semblait utile de développer un outil centré sur les capacités spontanées du nourrisson à susciter des interactions à la fois comportementales et émotionnelles avec son partenaire privilégié, plutôt que de se concentrer sur quelques comportements isolés ou des compétences générales de l’enfant.

La grille PREAUT a été développée à cet effet et a été testée à l’âge de neuf mois sur des nourrissons diagnostiqués syndrome de West et donc à haut risque de TSA.

Les bébés dépistés positifs se sont avérés avoir un risque de développer un TSA ou une DI à l’âge de quatre ans, égal à 38 fois celui des bébés négatifs.

L’outil a ainsi montré une excellente valeur prédictive positive (VPP), mais seulement sur un petit échantillon de nourrissons avec syndrome de West. Les résultats sur des échantillons d’enfants à risque élevé ne peuvent pas être directement généralisés sur la population générale (à faible risque).

L’étude PREAUT

L’étude PREAUT

Dans la présente étude, nous avons évalué la capacité de la grille PREAUT à prédire le risque de TSA au cours de la première année de la vie dans la population générale.

Nous avons examiné les bébés à 4, 9 et 24 mois, car ils sont systématiquement examinés à ces trois âges dans le suivi pédiatrique de routine en France.

Le but était de mettre en place une procédure de dépistage le plus précoce possible, réalisable dans le cadre du suivi médical habituel des nourrissons, ouvrant la voie à des soins préventifs précoces pour les enfants identifiés à risque.

La CHAT, qui était le meilleur outil validé au moment du démarrage de notre étude, a été utilisé pour le 24ème mois.

Nous avons fait l’hypothèse que :

1) un dépistage positif précoce à la grille PREAUT prédirait un dépistage positif ultérieurement à la CHAT ;

2) un dépistage positif précoce à la grille PREAUT prédirait un TSA entre trois et quatre ans, et

3) l’utilisation répétée de plusieurs outils améliorerait la sensibilité et la spécificité du processus de dépistage.

Méthode de l’étude

Concept de l’étude et participants

Dans cette étude prospective et multicentrique, les nourrissons ont été recrutés dans les centres de PMI (Protection Maternelle et Infantile) de 10 départements de France métropolitaine et d’Outre-mer entre Septembre 2005 et Novembre 2011.

Une étude pilote a été menée avant 2005 pour évaluer la faisabilité de former de nombreux médecins à coter et à utiliser dans leur pratique habituelle les outils de dépistage PREAUT et CHAT.

Les nourrissons sont systématiquement examinés à 4, 9 et 24 mois dans le suivi pédiatrique de santé en France.

Le service de PMI (santé publique) a été conçu pour permettre à toutes les familles, y compris celles de milieux défavorisés, d’accéder à une prévention et des soins médicaux gratuits. Aucune donnée sociodémographique n’a été collectée.

Le seul critère d’inclusion était d’être un enfant suivi par un service PMI, et les critères d’exclusion étaient le non-consentement des parents aux évaluations de suivi et/ou au protocole de recherche.

Les parents ont donné un consentement éclairé verbal après avoir reçu des informations verbales et écrites sur l’étude par le médecin assurant l’inclusion de l’enfant.

Le Comité de Protection des Personnes de l’Hôpital de Saint Germain en Laye a donné son autorisation au déroulement de l’étude le 14 Décembre 2000. Nous avons examiné 12 179 bébés avec la grille PREAUT à quatre mois (PREAUT-4) et / ou à neuf mois (PREAUT-9). Sur ce total, 4 835 enfants ont pu être examinés avec la CHAT à 24 mois (CHAT-24).

Outils de dépistage

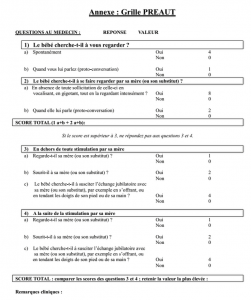

La grille PREAUT

La grille PREAUT a été développée à partir de l’observation de films familiaux de bébés plus tard diagnostiqués autistes, et du matériel clinique fourni par le travail thérapeutique auprès des nourrissons à risque.

Laznik a émis l’hypothèse que les bébés qui risquent de développer un TSA pourraient présenter un déficit du besoin inné d’échanger et d’être une source de plaisir pour la personne avec laquelle ils interagissent, contrairement aux nourrissons en bonne santé.

La grille PREAUT évalue la capacité du nourrisson à s’engager spontanément et de manière synchrone dans des interactions ludiques et jubilatoires.

Les items de la grille PREAUT (par exemple : le bébé regarde-t-il l’examinateur / sa mère (ou son substitut) – spontanément, ou seulement s’il est sollicité ?) ont été formulés afin de cibler le manque d’initiative sociale : en effet, plus un bébé est spontanément et activement engagé dans l’interaction, meilleur est son score PREAUT.

La grille est cotée par le médecin lors de la visite habituelle du nourrisson avec sa mère (ou son substitut). Le médecin observe comment le bébé se comporte avec lui et avec sa mère, non seulement quand il est sollicité mais aussi quand personne ne le sollicite directement.

La grille est fournie en annexe.

Elle comprend une première partie de quatre items et une deuxième partie de six items complémentaires.

La deuxième partie n’est complétée que si le nourrisson a montré des comportements à risque aux quatre premiers items (score à la première partie

A 3 mois, le seuil pathologique du risque a été fixé à

Par contre, à 9 mois, nous avions constaté dans une étude exploratoire en population générale, que très peu de nourrissons atteignaient ce seuil (seulement trois nourrissons positifs, dont 1 cas de TSA). Ainsi, à 9 mois, nous avons décidé de relever le seuil à

Ainsi, avec ce nouveau seuil, le nourrisson de neuf mois est considéré « à risque » s’il n’a pas d’initiative avec sa mère et ne répond pas non plus aux tentatives de sa mère de l’engager dans l’interaction, et ceci même s’il a regardé l’observateur, alors que le nourrisson de quatre mois était considéré comme n’étant pas à risque dès lors qu’il avait regardé spontanément l’observateur.

La CHAT (Checklist for Autism in Toddlers)

L’échelle CHAT est un instrument de dépistage du risque d’autisme chez des enfants de 18 à 24 mois évaluant leurs comportements habituels et modalités de jeu.

Elle comprend neuf questions proposées aux parents (items A), évaluant l’intérêt de l’enfant pour les interactions sociales, les jeux moteurs, le jeu de faire semblant, le pointage, le fait d’apporter un objet pour le montrer (recherche d’attention conjointe), et cinq questions d’observation évaluant le comportement de l’enfant et les réactions aux stimuli initiés par l’examinateur (items B: échange de regards, jeu de faire semblant, pointage proto-déclaratif, compréhension du pointage et construction d’une tour de cubes).

Les nourrissons sont considérés comme étant à risque élevé quand ils échouent aux cinq items-cibles. Les nourrissons sont considérés comme « positifs » avec un risque moyen, lorsqu’ils ne pointent jamais (pointage proto-déclaratif), ni selon leur mère (A7) et ni lors de l’observation par l’examinateur (B4).

Nous avons retenu le seuil du niveau de risque moyen pour avoir une meilleure sensibilité.

La CHAT a été administrée à l’âge de 24 mois pour coïncider avec le calendrier d’examens systématiques du suivi pédiatrique en France.

Déroulement de l’étude

Déroulement de l’étude

Première étape de l’étude : la formation des équipes médicales

La première étape de l’étude a consisté à former aux outils de dépistage environ six cents pédiatres et médecins généralistes travaillant dans les services de Protection Maternelle et Infantile (PMI) de dix départements métropolitains et d’outre-mer.

La formation de trois journées comprenait une actualisation de connaissances générales sur l’autisme, la présentation des objectifs et de la méthodologie de l’étude, ainsi que les outils de dépistage utilisés. Les praticiens ont participé à des jeux de rôle dans des petits groupes pour apprendre à utiliser les instruments. Des sessions de cotation sur support vidéo ont été réalisées afin de les entraîner et évaluer leur capacité à utiliser les outils.

Deuxième étape de l’étude : l’inclusion de l’échantillon de bébés

La deuxième étape visait à inclure au moins 10 000 bébés afin d’atteindre une puissance statistique suffisante compte-tenu d’un taux de perdus de vue de 50% au fil des deux années du protocole de dépistage.

Au cours de la première année de déroulement du protocole, 12 179 nourrissons ont été examinés avec la grille PREAUT à quatre et/ou à neuf mois, dont 8 933 ont pu être examinés aux deux âges.

Sur les 12 179 bébés examinés avec la grille PREAUT pendant la première année, seuls 4 835 enfants ont passé la CHAT à 24 mois, ce qui indique que 7 342 enfants ont été perdus de vue au cours du suivi avant la visite des deux ans. Deux bébés ont été exclus en raison d’un décès prématuré et d’un polyhandicap.

Il n’y avait pas de différence significative entre les nourrissons qui ont eu le dépistage avec la CHAT et ceux perdus de vue lors de l’évaluation à 24 mois, pour le sexe ou l’âge à la première évaluation PREAUT.

En revanche, il y avait une différence significative dans les scores de la grille PREAUT pour les enfants ayant obtenu un résultat positif à la première évaluation de la grille PREAUT, et qui avaient bénéficié d’un suivi précoce.

Troisième étape de l’étude : examen de sortie de protocole et recherche de faux négatifs

La troisième étape consistait à :

1) l’évaluation diagnostique entre trois et quatre ans pour les enfants ayant été positifs à l’un des examens de dépistage, moyennant l’application d’un examen de sortie de protocole,

2) l’estimation des faux négatifs.

L’examen de sortie de protocole

Un rendez-vous de suivi a été proposé aux 100 enfants ayant eu un score positif (à la grille PREAUT à 4 ou 9 mois et/ou à la CHAT à 24 mois).

Les étapes du développement étaient systématiquement tracées lors des visites pédiatriques obligatoires, incluant les paramètres périnataux (grossesse, accouchement, terme, poids de naissance, Apgar) ainsi que les antécédents médicaux (pour l’enfant et la famille).

Les médecins de PMI ont assuré un examen pédiatrique pendant la troisième ou la quatrième année de l’enfant, au cours de laquelle un psychologue qualifié a administré la CARS (Childhood Autism Rating Scale) et la WPPSI (Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence) ou le test de Brunet-Lézine. Le cas échéant, le psychologue évaluait cliniquement les symptômes de TSA pour établir un diagnostic clinique positif selon les critères de la CIM-10.

En plus de ce rendez-vous de suivi, les enfants positifs à n’importe quelle étape du dépistage ont été immédiatement orientés vers des services de soins spécialisés, qui ont fourni ultérieurement une évaluation clinique contribuant au diagnostic final.

En général, les recommandations françaises pour l’autisme rendent obligatoire l’utilisation d’un instrument standardisé, comme par exemple l’ADOS (Autism Diagnosis Observation Schedule) ou l’ADI (Autism Diagnostic Interview). Cependant, compte-tenu de la taille de l’échantillon, ces évaluations n’ont pas été effectuées par l’équipe de recherche mais plutôt par des services de soins spécialisés proches du domicile de la famille.

Si le diagnostic de TSA restait discutable, un pédopsychiatre de l’équipe de recherche a rassemblé des informations supplémentaires auprès des services de suivi et de la MDPH pour savoir si l’enfant bénéficiait d’aménagements scolaires particuliers.

Au total, 45 enfants (45%) ont reçu une estimation diagnostique à la fin de l’étude.

Il n’y a pas eu de différences significatives entre les enfants qui ont reçu un diagnostic estimé et ceux qui ont été perdus de vue par rapport au sexe ou à l’âge à la première évaluation de la grille PREAUT, ou le pourcentage d’enfants à risque après le dépistage par la CHAT.

En revanche, il y avait une différence significative dans les scores de la grille PREAUT, tels que les enfants positifs à la grille PREAUT avaient un meilleur taux de suivi que ceux qui n’avaient pas été dépistés positifs au cours de la première année.

Recherche des faux-négatifs

Nous avons tiré au sort 1 100 enfants parmi ceux négatifs à tous les instruments de dépistage afin d’évaluer leur évolution et identifier d’éventuels troubles neurodéveloppementaux (recherche de faux négatifs).

Les médecins de PMI participant à la recherche ont recueilli des informations concernant ces enfants à quatre ou cinq ans lors d’examens systématiques effectués à l’école (bilans de maternelle) ou dans le cadre d’un suivi.

La plupart ont bénéficié d’un « bilan de maternelle », incluant des aspects généraux de leur intégration à l’école et des aspects plus spécifiques de leur développement, tels que la motricité globale, image du corps, motricité fine, organisation de la perception, langage expressif et compréhension.

Si le diagnostic était discutable, un pédopsychiatre de l’équipe de recherche a obtenu des informations supplémentaires auprès des services de suivi en lien avec la MDPH.

Analyses statistiques

Pour accéder au détail de l’ensemble des calculs effectués sur les données de l’étude, le lecteur est invité à consulter l’article original.

Discussion des résultats

Discussion des résultats

Le but de cette étude était d’examiner la capacité de la grille PREAUT à détecter un risque de TSA à un stade de développement très précoce en population générale (faible risque).

Nous avons recruté prospectivement 12 179 enfants, et 4 835 ont complété le protocole à 24 mois.

Aux cent enfants positifs à l’un des examens de dépistage il a été proposé dans la troisième année de vie l’examen de sortie de protocole : une évaluation clinique (comprenant la CARS, un quotient de développement, et un diagnostic clinique selon la CIM-10 si approprié).

Sur les 100 enfants dépistés positifs, 45 ont pu être suivis et bénéficier d’une évaluation diagnostique.

Parmi ceux-ci, 22 étaient en bonne santé, 10 ont reçu un diagnostic de TSA, 7 avaient une déficience intellectuelle (DI), et 6 avaient un autre trouble du développement.

50% des nourrissons positifs à l’un des examens de dépistage ont ensuite reçu un diagnostic neurodéveloppemental.

Ainsi, la grille PREAUT a été capable d’identifier un risque précoce d’autisme et autres troubles neurodéveloppementaux dans ce vaste échantillon.

Nous avons aussi examiné les associations significatives entre un score positif à la grille PREAUT et chaque item de la CHAT : un score positif à quatre ou neuf mois à la grille PREAUT prédit un score de risque à la CHAT à 24 mois avec une forte probabilité.

La sensibilité et la valeur prédictive positive (VPP) pour les deux outils de dépistage étaient à peu près similaires (sensibilité d’environ 30%, VPP d’environ 25%), même si le dépistage avec la grille PREAUT a été effectué 15 à 20 mois plus tôt qu’avec la CHAT.

Les résultats de notre étude montrent que :

- l’utilisation répétée des instruments de dépistage et/ou leur association a augmenté leur sensibilité en la portant au-dessus de 70% : les 2/3 des cas de TSA ont été détectés à 24 mois, et

- la moitié des cas de TSA étaient détectés en fait dès l’âge de 9 mois grâce à la répétition du dépistage PREAUT à 4 et à 9 mois.

Nous avions déjà montré la capacité de la grille PREAUT à prédire les cas de TSA dès la première année de vie, dans une étude antérieure sur des nourrissons à haut risque avec syndrome de West.

Dans la présente étude, la grille PREAUT a été en mesure de prédire correctement un diagnostic de TSA dans une proportion notable (un vrai TSA sur quatre bébés positifs), alors qu’elle était utilisée en population générale, dans laquelle la prévalence des TSA est relativement faible. De plus, de nombreux enfants « faux positifs » ont en fait reçu un autre diagnostic de trouble du développement, la DI étant le plus fréquent.

Ainsi, le taux de vrais positifs passe à un sur deux pour dépister un trouble neurodéveloppemental global (TSA + DI), car la moitié des nourrissons dépistés positifs à l’âge de quatre mois ont plus tard reçu un diagnostic de DI ou TSA.

Ces résultats neurodéveloppementaux pourraient justifier une intervention très précoce.

Dans leur étude, Jones et Johnson, faisant valoir qu’il existe une variabilité importante des trajectoires de développement précoce, ont proposé que l’intervention précoce devrait cibler « les mécanismes neurodéveloppementaux qui produisent des symptômes cliniques au cours du développement précoce », sans attendre le diagnostic clinique. Cela pourrait « à long terme améliorer ou même prévenir l’apparition des symptômes » .

Enfin, la grille PREAUT a démontré son utilité dans les mains des professionnels formés dans les services pédiatriques de prévention et d’accueil et d’accompagnement de la petite enfance. Ainsi, cet outil peut être utile pour élaborer des stratégies de détection précoce des TSA ou d’autres troubles neurodéveloppementaux, et mettre en place des soins les plus précoces possibles, ce qui est crucial pour le pronostic.

Les bébés positifs à la grille PREAUT devraient être examinés avec soin et être pris en charge pour favoriser au maximum le développement de leurs capacités interactives.

D’autres études le montrent

Ces dernières années, plusieurs auteurs ont tenté d’évaluer les avantages d’une intervention très précoce sur des bébés à risque d’autisme. Voir la revue de la littérature faite par Bradshaw et coll., en 2015.

Par exemple, un essai randomisé en aveugle auprès de bébés âgés de 7 à 10 mois à risque d’autisme a suggéré que 6 à 12 séances d’intervention à domicile avec les parents permettait d’augmenter l’attention du nourrisson aux parents, de réduire les marqueurs comportementaux de risque autistique et d’améliorer le désengagement de l’attention.

Une autre étude a suggéré qu’une dizaine d’interventions précoces à domicile incluant les parents avait « le potentiel d’impacter les systèmes cérébraux qui sous-tendent l’attention sociale chez les bébés à risque familial de TSA ».

Ces dernières études ont été menées avec les frères et sœurs non symptomatiques, dont le risque pour l’autisme est estimé jusqu’à 20%.

Or, dans notre étude, des enfants positifs à P4 ou P9 avaient un risque d’autisme supérieur à 20%. Il semble donc raisonnable de proposer une détection très précoce suivie d’une intervention pour les bébés à risque.

De plus, il est possible que l’intervention précoce, dont le but est d’intensifier la sensibilité des parents aux signaux émis par le nourrisson, puisse être en mesure de prévenir ou du moins atténuer, non seulement la symptomatologie des TSA, mais aussi d’autres troubles neurodéveloppementaux que nous avons trouvé associés à un résultat positif à la grille PREAUT.

Comparaisons avec d’autres outils et études

Compte-tenu du nombre d’études sur le dépistage de TSA, nous avons limité notre comparaison aux études prospectives, qui ont évalué des instruments de dépistage au cours des deux premières années de vie, et sur un échantillon de la population générale.

Les outils de dépistage les plus étudiés dans la deuxième année de vie sont la CHAT et la M-CHAT.

Dans notre étude nous avons utilisé la CHAT, alors que la M-CHAT aurait pu avoir une meilleure sensibilité, mais elle n’était pas encore validée en 2005 lorsque nous avons commencé notre étude.

En tout état de cause, le dépistage combiné grille PREAUT dans la première année + M-CHAT à 18 ou 24 mois devrait être plus sensible que le dépistage combiné PREAUT + CHAT, donc cette association est à considérer pour les programmes de dépistage systématique en population générale.

Ces résultats confirment que la mise en œuvre des programmes de dépistage précoce, à l’aide d’une démarche en deux étapes pourrait être cliniquement pertinente et conduire à une détection plus précoce des TSA.

Implications pour le dépistage précoce des TSA

Nos résultats suggèrent le développement d’une nouvelle stratégie de dépistage et de diagnostic des enfants à risque de troubles neurodéveloppementaux.

Premièrement, nous pensons qu’un dépistage précoce devrait, au mieux, détecter un risque de développer des troubles du neurodéveloppement, dont les TSA.

Les tests de dépistage devraient être proposés largement à un âge précoce. Ils ne doivent pas fournir un diagnostic définitif, mais indiquer la possibilité d’un trouble du développement qu’il est peut-être trop tôt pour identifier.

Il est donc nécessaire de suivre les enfants jusqu’à l’âge de trois ou quatre ans avec une évaluation détaillée pour confirmer ou exclure le diagnostic initial.

Cependant, l’identification de signes d’alerte précoce des troubles neurodéveloppementaux devrait conduire à une évaluation spécialisée des interactions du bébé et pourrait justifier des soins d’accompagnement sans attendre le diagnostic final.

Deuxièmement, nos résultats et ceux d’autres études suggèrent qu’une approche dyadique des interactions tenant compte à la fois de la synchronie et des émotions pourrait être utile pour évaluer précocement le risque de TSA dans la première année de vie, et met en lumière l’importance de considérer simultanément les deux dimensions plutôt que de les considérer comme s’excluant mutuellement.

Les parents peuvent être d’excellents informateurs des processus pathologiques qui se produisent chez leur enfant en développement.

Troisièmement, nos résultats confortent l’idée qu’un dépistage répété pourrait représenter la meilleure stratégie pour augmenter la sensibilité, dont la valeur est souvent la plus faible dans le domaine du diagnostic précoce des TSA.

Les instruments doivent être adaptés aux capacités développementales et les outils de la première année et ne devraient pas être les mêmes que ceux de la deuxième année.

Durant la première année, les instruments avec une évaluation dyadique pourraient avoir une valeur ajoutée.

Limites de l’étude

Notre étude a cependant plusieurs limites.

Tout d’abord, elle a été affectée par une perte considérable de l’échantillon de départ. Nous avons perdu environ la moitié des enfants à chaque étape de l’étude.

Le fait que les centres de PMI reçoivent un nombre important de familles appartenant aux catégories socio-professionnelles défavorisées, souvent de diverses origines culturelles, peu ou pas francophones, a peut-être contribué au nombre élevé de familles perdues de vue au fil du protocole.

Malgré cela, il est important de mettre en œuvre des actions de recherche dans des conditions de terrain visant à élaborer des stratégies de dépistage qui puissent toucher des populations qui ont peu accès à des soins privés.

Nous ne pouvons pas exclure un biais possible ou une différence aléatoire entre les échantillons suivis et perdus.

Nous avons fait l’hypothèse que l’échantillon d’enfants négatifs perdus de vue était semblable à celui qui a été effectivement suivi.

Deux facteurs sont en faveur de cette hypothèse :

1) la comparaison entre les données des enfants suivis et celles des enfants perdus de vue ne montre pas de différence significative en âge ou sexe, et

2) la prévalence des TSA (0,56 à 0,74%) sur la base de ces estimations est concordante avec la prévalence attendue (0,67%) d’après les études épidémiologiques.

Une autre limite de notre étude est que les TSA n’ont pas toujours été évalués à l’aide d’outils de diagnostic « gold standard », comme l’ADI-R ou l’ou ADOS.

Nous n’avons pas toujours pu organiser des évaluations directes en raison de la grande dispersion géographique de notre échantillon – plus de 10 départements français métropolitains et d’outre-mer participaient à l’étude.

Cependant, l’utilisation d’informations émanant d’équipes de soins psychiatriques ou parfois des psychologues scolaires, a fourni une description suffisamment détaillée des symptômes de l’enfant et de ces éventuelles déficiences fonctionnelles, ce qui a permis d’établir un diagnostic en adéquation avec les critères de la CIM-10.

En revanche, cette étude portant sur l’autisme, les faux négatifs ont généralement été moins bien évalués pour la DI, et la possibilité d’un diagnostic final de DI parmi les négatifs a été insuffisamment investiguée.

Troisièmement, nous n’avons pas pu évaluer l’effet des interventions précoces sur les résultats des enfants, car cela n’a pas été systématiquement tracé.

Cependant, du point de vue des « cascades développementales », il est probable que le suivi et l’accompagnement cliniques à cet âge précoce aient pu influencer les trajectoires développementales des enfants.

Enfin, le test de dépistage à 24 mois était la CHAT, connue pour être moins sensible que la M-CHAT, mais celle-ci n’était pas encore validée au moment où notre étude a commencé.

D’autres études devraient répliquer et confirmer ces résultats, en population générale ou sur d’autres populations à risque (comme les fratries), en utilisant la M-CHAT à 18 ou 24 mois. Elles devraient également mieux suivre l’effet potentiel des interventions sur le devenir et proposer des outils d’évaluation plus standardisés, tels que l’ADI-R et l’ADOS.

L’importance des enfants perdus de vue au fil du suivi pourrait aussi être diminuée si les registres des MDPH étaient disponibles en France pour la recherche, comme cela se pratique dans d’autres pays. A l’heure actuelle, ces registres sont disponibles dans seulement deux départements en France.

Conclusion & Remerciements

Conclusion

Le but de cette étude était d’examiner la validité de la grille PREAUT comme outil de dépistage des bébés à risque de TSA en population générale.

Nos résultats permettent d’envisager l’utilisation de la grille PREAUT pour le dépistage très précoce des TSA et d’autres troubles du développement en population générale, rendant possible l’identification des nourrissons et familles requérant un soutien précoce, afin de réduire l’impact de l’installation d’un TSA ou d’une DI.

La répétition du dépistage avec des outils d’approches différentes, a permis une augmentation significative de la sensibilité du dépistage.

Nos résultats indiquent également que l’évaluation interactive (synchronie et émotion) peut aider à détecter le risque de TSA à un stade très précoce du développement de l’enfant.

Les acteurs de santé sont essentiels pour détecter des problèmes développementaux au plus tôt, y compris les TSA, au cours d’un suivi régulier du développement, de façon à permettre aux enfants d’accéder plus tôt à des interventions précoces et adaptées.

Remerciements

Les auteurs remercient vivement les enfants et leurs familles ayant accepté de participer à l’étude, ainsi que les équipes médicales l’ayant rendue possible.

Contributions d’auteur

Conceptualisation : Marie-Christine Laznik, Claude Bursztejn, David Cohen

Collecte de données : Graciela Crespin, Jean-Louis Sarradet, Colette Bauby, Anne-Marie Dandres, Jean Xavier, Nicolas Bodeau

Analyse formelle : Bertrand Olliac, Nicolas Bodeau

Obtention de fonds : Graciela Crespin, Jean-Louis Sarradet, Claude Bursztejn

Enquête : Graciela Crespin, Colette Bauby, Anne-Marie Dandres, Emeline Ruiz, Jean

Xavier, Catherine Saint-Georges

Méthodologie: Claude Bursztejn, David Cohen, Catherine Saint-Georges

Administration du projet : Graciela Crespin, Jean-Louis Sarradet, David Cohen, Catherine

Saint-Georges

Ressources : Graciela Crespin, Jean Xavier

Logiciel : Oussama Cherif El Idrissi Ganouni

Supervision : Graciela Crespin, Bruno Falissard, David Cohen

Rédaction – projet original : Bertrand Olliac, Catherine Saint-Georges

Rédaction – Révision et édition : David Cohen, Catherine Saint-Georges.

Pour les références bibliographiques complètes, se référer à l’article original chez PLOS ONE.

Présentation du signe PREAUT

Le signe PREAUT

-

-

-

- C. Laznik propose son hypothèse de signe PREAUT: Il y aurait, chez le bébé à risque d’évolution autistique, un ratage du troisième temps du circuit pulsionnel, c’est-à-dire une non-apparition de la capacité à initialiser les échanges sur un mode ludique et jubilatoire.

-

-

De nombreux travaux montrent que le bébé a, dès la naissance, un intérêt pour des éléments spécifiques de la voix de la mère (pulsion invocante). C’est le phénomène du mamanais. Au cours de la première année de la vie, le bébé montre aussi un vif intérêt à regarder et être regardé (pulsion scopique), et pour les jeux à manger et être mangé pour rire (pulsion orale). L’ensemble de ces échanges sont facilement observables pour le pédiatre.

Dans sa description du circuit pulsionnel, Freud avait postulé qu’il y avait trois temps :

-

-

-

- 1° temps: Actif, le bébé va vers l’objet de satisfaction;

-

-

-

-

-

- 2° temps: Auto-érotique, le bébé prend une partie de son corps comme objet de satisfaction;

-

-

-

-

-

- 3°temps: dit de passivation pulsionnelle, le bébé se fait l’objet de satisfaction pulsionnelle de son autre familier (sa mère ou son substitut)

-

-

Voici comment se présentent, à l’observation, les trois temps dans le circuit pulsionnel oral:

-

-

-

- Dans le premier temps, actif, le bébé va vers l’objet, sur le plan oral: le sein ou le biberon

-

-

-

-

-

- Dans le deuxième temps, auto-érotique, le bébé prend une partie de son corps comme objet, sur le plan oral : les doigts ou la tétine

-

-

Ces deux temps, bien connus, sont déjà observés par les médecins, qui leur attribuent, à juste titre, une grande importance dans le développement de l’enfant.

Mais le troisième temps du circuit pulsionnel oral est moins connu et risque de ce fait de ne pas être aussi souvent observé ; il se présente comme suit :

-

-

-

- Le bébé offre une partie de son corps pour que sa mère « goûte» si c’est bon

-

-

-

-

-

- La mère joue à faire semblant de goûter: « On en mangerait du bébé comme ça!»

-

-

-

-

-

- Le bébé montre sa joie d’avoir suscité la jouissance qu’il lit sur le visage (pulsion scopique) et dans la voix (pulsion invocante) de sa mère.

-

-

De nombreux films familiaux montrent ce type d’échanges spontanés entre les mères et les bébés bien portants au cours des repas, du change ou du bain.

Les scènes suivantes sont extraites des vidéos familiales utlisées par PREAUT dans la formation des médecins, et qui montrent comment un bébé bien portant, Fabien, cherche à provoquer la réaction jubilatoire de sa mère, alors que Marco, un bébé devenu autiste, ne le fait pas.

-

-

-

- Fabien, 5 mois, est avec sa mère ;

-

-

-

-

-

- Elle joue à « le manger»

-

-

-

-

-

- Il lui tend ses doigts et son pied pour qu’elle « goûte si c’est bon»

-

-

-

-

-

- La mère joue à goûter, et dit, joyeusement: « On en mangerait du bébé comme ça !»

-

-

Alors Fabien relance l’interaction, lui offrant à nouveau ses pieds « à goûter », pour qu’elle recommence :

Finalement Fabien montre sa joie d’avoir causé le plaisir qu’il lit dans le visage de sa mère (pulsion scopique), et dans sa voix (pulsion invocante):

Le deuxième temps n’est auto-érotique que si le troisième existe. En effet, il faut ce temps de plaisir partagé pour que le recours au corps propre – sucer ses doigts ou la tétine -, deuxième temps du circuit pulsionnel, devienne réellement “auto-érotique”.

Les bébés en risque d’autisme peuvent avoir des mouvements de succion qui sont des procédures auto-calmantes, sans pour autant être auto-érotiques. Ce qu’il semble manquer dans leur cas, c’est l’inscription de cette jubilation partagée dans l’échange avec son autre familier (habituellement, ses parents), et ce, quelle que soit la raison de cette défaillance (déficit d’équipement du bébé, déficit environnemental).

Les films familiaux nous apprennent aussi que même les bébés en risque d’autisme peuvent répondre parfois en regardant et souriant en situation de «protoconversation», mais qu’ils ne cherchent jamais à susciter l’échange dans le quotidien.

Dans les scènes qui suivent de la vidéo familiale PREAUT, Marco ne cherche pas à susciter l’échange dans les situations quotidiennes, même s’il est capable de répondre en situation de « proto-conversation » telle que décrite par C. Trevarthen.

Marco, à 2 mois et demi, répond en souriant et regardant ses parents en situation de « proto-conversation » :

Par contre, il ne regarde pas ni cherche à se faire regarder pendant les scènes quotidiennes de change ou du bain :

Par conséquent, dans la recherche PREAUT, nous considérons que le clignotant de risque s’allume quand le bébé ne cherche pas à susciter le regard pour le plaisir, ni par sa mère ni par le médecin, alors qu’il n’est pas spécifiquement sollicité pendant la consultation pédiatrique de routine de 4 et 9 mois. Les bébés bien portants montrent bien avant 4 mois ce plaisir à susciter le regard de leurs proches.

En conséquence, le signe PREAUT résulte de la combinaison de ces deux comportements, habituellement présents très tôt chez les bébés bien portants :

-

-

-

- le bébé ne cherche pas à se faire regarder par sa mère (ou son substitut), en absence de toute sollicitation de celle-ci,

-

-

-

-

-

- le bébé ne cherche pas à susciter l’échange jubilatoire avec sa mère (ou son substitut), en absence de toute sollicitation de celle-ci

-

-

Summary

Abstract

Background

The need for early treatment of autism spectrum disorders (ASD) necessitates early screening. Very few tools have been prospectively tested with infants of less than 12 months of age. The PREAUT grid is based on dyadic assessment through interaction and shared emotion and showed good metrics for predicting ASD in very-high-risk infants with West syndrome.

Methods

We assessed the ability of the PREAUT grid to predict ASD in low-risk individuals by prospectively following and screening 12,179 infants with the PREAUT grid at four (PREAUT-4) and nine (PREAUT-9) months of age. A sample of 4,835 toddlers completed the Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (CHAT) at 24 months (CHAT-24) of age. Children who were positive at one screening (N = 100) were proposed a clinical assessment (including the Children Autism Rating Scale, a Developmental Quotient, and an ICD-10-based clinical diagnosis if appropriate) in the third year of life. A randomly selected sample of 1,100 individuals who were negative at all screenings was followed by the PMI team from three to five years of age to identify prospective false negative cases. The clinical outcome was available for 45% (N = 45) of positive children and 52.6% (N = 579) of negative children.

Results

Of the 100 children who screened positive, 45 received a diagnosis at follow-up. Among those receiving a diagnosis, 22 were healthy, 10 were diagnosed with ASD, seven with intellectual disability (ID), and six had another developmental disorder. Thus, 50% of infants positive at one screening subsequently received a neurodevelopmental diagnosis. The PREAUT grid scores were significantly associated with medium and high ASD risk status on the CHAT at 24 months (odds ratio of 12.1 (95%CI: 3.0–36.8), p < 0.001, at four months and 38.1 (95%CI: 3.65–220.3), p < 0.001, at nine months). Sensitivity (Se), specificity, negative predictive values, and positive predictive values (PPVs) for PREAUT at four or nine months, and CHAT at 24 months, were similar [PREAUT-4: Se = 16.0 to 20.6%, PPV = 25.4 to 26.3%; PREAUT-9: Se = 30.5 to 41.2%, PPV = 20.2 to 36.4%; and CHAT-24: Se = 33.9 to 41.5%, PPV = 27.3 to 25.9%]. The repeated use of the screening instruments increased the Se but not PPV estimates [PREAUT and CHAT combined: Se = 67.9 to 77.7%, PPV = 19.0 to 28.0%].

Article

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) consists of a heterogeneous group of neurodevelopmental disorders [1] that are characterized by disturbances in social relationships and communication, repetitive behaviors and narrow interests, and several degrees of severity [2]. Epidemiological studies have reported a recent increase in prevalence, but this is still a matter of debate. This increase is likely attributable to extrinsic factors, such as improved awareness and recognition of the disease, as well as changes in diagnostic practices and the availability of special services [3, 4] and, in part, expansion of the diagnostic criteria [5, 6]. In 2010, the overall prevalence of ASD among eight-year-old children in the United States was 14.7 per 1,000 or one in 68 [7]. In France, the most recent study, based on the handicap registry, reported an overall prevalence rate of 35/10,000 for ASD among children of the same age group [8].

It is commonly accepted that children with ASD should be enrolled in treatment programs as early as possible [9–14]. The goals of these early interventions are to increase adaptive communication and socialization behaviors, decrease maladaptive behaviors, reduce distress, and increase the quality of life [15, 16]. Some authors argue that very early treatment in infants could inflect the deviant trajectory before installation of the full autistic syndrome and even prevent autism [9]. Indeed, recent studies have attempted to assess the feasibility, effectiveness, and benefits of very early intervention with parents and infants at risk for autism, with encouraging results [17–20]. However, the need for early treatment necessitates the development of tools that allow screening (or the detection of at-risk children) as early as possible [21].

The minimum age for reliable early diagnosis of ASD encompasses several research questions. Although the symptoms of ASD are often present early in life [22–25], the diagnosis of ASD is generally made between the ages of three and five years [24, 26–28]. There are at least five contributing factors that explain this situation: (1) parental concern is not sufficiently taken into account [23, 29–31], (2) the onset of ASD sometimes occurs after the second year of life [32, 33], (3) infants are not developmentally mature enough to meet the diagnostic criteria, (4) differential diagnosis issues are complex at an early age (this is particularly relevant for severe language impairment and intellectual disability, ID), and (5) diagnosis is risky before the age of two years because it is more likely be unstable [34]. The diagnostic criteria of ASD have changed in recent years [35]. Some authors suggest that the present classification system and other factors may contribute to the increasing instability of community-assigned labels of ASD [36]. The initial diagnosis may evolve toward recovery or delayed development without autistic traits. Indeed, early detection cannot be isolated from the possibility of interference with the outcome, as the detected children are more likely to receive support. Some authors suggest that early intervention could diminish autistic symptoms and improve developmental outcomes for a significant proportion of children, and may even be able to reverse the secondary processes of autism [9], or prevent the installation of ASD [17].

Since Baron-Cohen tested the Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (CHAT) on 18 month-old children [37], several studies have attempted to develop screening tools, most often for at-risk toddlers (e.g., children who are evaluated for suspected autism, siblings of such children, and infants with genetic diseases) or toddlers who have already been diagnosed with ASD through clinical judgment and other validated tools (e.g., the Autism Diagnostic Interview, Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, and Childhood Autism Rating Scale). These types of studies face several challenges [38]. First, studies with at-risk infants tend to produce much higher positive predictive values (PPVs) than community-based screening studies, because a higher prevalence rate implies a higher probability for a positive result to be correct [39]. In contrast, studies of the general population need to screen a very large sample to obtain enough positive diagnoses in childhood. Many studies cannot assess the sensitivity and specificity of the screening tool because they only assess children who screened positive, which does not capture false negative cases [38]. These studies estimate accuracy with a PPV (calculated from the observed false positive rate) and evaluate sensitivity by calculating the difference between the observed and theoretical prevalence rates. In addition to the accuracy of the tool, early screening is confronted with another issue: the uncertain stability of ASD before the age of two years [40].

Screening tools for toddlers during the second year of life include the CHAT [41, 42] or a modified version of the CHAT, including the M-CHAT (Modified-CHAT)) [43, 44] and the Q-CHAT (Quantitative-CHAT) [45]; the Checklist for Early Signs of Developmental Disorders (CESDD) [46]; the Brief Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment Questionnaire (BITSEA) [47]; the Young autism and other developmental disorders Checkup Tool at 18 months (Yacht 18) [48], the Social Attention and Communication Study (SACS) [49]; the Early Screening of Autistic Traits Questionnaire (ESAT) [50], and the Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ) [51]. The CHAT was found to have a good specificity, but low sensitivity [52]; the M-CHAT showed better sensitivity, but produced many false positive scores. More recently, a new two-stage M-CHAT procedure, with follow-up interview, detected potentially indicative psychometric values in a low-risk sample [44]. Researchers are now trying to screen for autism at a very early age.

Few tools have been tested prospectively on infants as young as 12 months. Two have been developed for, or tested on, at-risk siblings. 1) The Autism Observation Scale for Infants (AOSI) is a behavioral observation scale that was shown to predict autism in at-risk siblings who were 12 and 14 months old, but failed to predict the outcome at six and seven months of age [53, 54]. 2) The First Year Inventory (FYI), a parental questionnaire, also showed promising results [55]. Three tools have been assessed in the community. 1) The FYI has been used in a population-based study with a small sample [56, 57]. 2) The SACS is a behavioral inventory that reported striking results for the screening of 12-month-old infants in the community [49], but failed to be confirmed by further research. 3) The Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales Developmental Profile Infant-Toddler Checklist (CSBS-DP IT-Checklist) is a parental questionnaire that demonstrated high specificity, but low sensitivity and PPV [58, 59].

Only three tools have been prospectively tested and shown to have predictive value for children of less than one year of age. 1) The CSBS-DP IT-Checklist was used to screen the general population at 6 to 8 and 9 to 11 months of age [60] and 2) the Taiwan Birth Cohort Study (TBCS) screened six-month-old infants in the community [61]; both tools showed a low PPV. 3) The PREAUT (Programme de Recherches et d’Etudes sur l’AUTisme) grid was developed to screen very early at-risk infants.

Several authors have proposed a paradigm shift from the assessment of infant behavior to dyadic assessment of interactions, because delays in developmental milestones and impairments in early social interactions are not sufficient to predict ASD. They argue that early screening of ASD should rely on dyadic/interactive behaviors, rather than infant/toddler behaviors. The developmental cascades perspective suggests that dysfunction in one system can influence another system over time to shape the course of development [62]. Recent studies in ASD, using a retrospective approach through home movies [25, 63–65] or a prospective approach with at-risk samples (e.g., siblings [66–69]), provide support for this shift by examining the quality of early interactions through synchrony, reciprocity, and emotional engagement [70]. Indeed, mothers of at-risk infants try to compensate for the lack of interactivity of their child by intensifying their stimulation from very early on [65]. Green proposed that interactive specificities of infants at risk for autism may modify parents’ behavior in interactive cycles [71].

Thus, it appeared necessary to develop a tool that focused on the infant’s spontaneous ability to provoke both behavioral and emotional interactions with its care-giver [70], rather than focusing on a few isolated infant behaviors or general skills. The PREAUT grid was developed for this purpose and was tested at nine months of age on infants who had West syndrome and were at high risk for ASD [72]. Patients who screened positive had a risk of developing ASD or ID at age four. The tool showed a good PPV, but only in a small sample of at-risk infants who had West syndrome [72]. Findings from samples of high-risk children might not be generalizable to the low-risk population [73]. Here, we assessed the ability of the PREAUT grid to predict ASD during the first year of life in the community. We screened the children at 4, 9, and 24 months of age, as infants are systematically examined at these three ages in France. The goal was to implement a feasible screening procedure, beginning as early as possible, that could open the way to preventive care for at-risk children. The M-CHAT revised with follow-up was not validated when our study began. Thus, we used the CHAT for the 24-month screening, as it was the best validated tool at that time. We hypothesized that (1) an early positive PREAUT screen would predict a later positive CHAT screen; (2) an early positive PREAUT screen would predict ASD at three to four years of age; and (3) multiple screens would improve sensitivity and specificity of the detection process.

Methods

Design and participants

In this prospective multi-centric study, infants were enrolled in the PMI centers of 10 French departments between September 2005 and November 2011. A pilot study was conducted before 2005 to assess the feasibility of training many PMI (Mother/Infant Protection) physicians to use and score screening tools (PREAUT and CHAT) in their current practice. Infants are systematically examined at 4, 9, and 24 months of age in the French healthcare system. The PMI system was designed to allow all families, including those of low socio-economic status, to access free medical care and prevention. No socio-demographic data were collected. The only inclusion criterion was being a child entering a PMI service. Exclusion criteria were parents’ refusal to consent to the follow-up assessment and/or the research protocol. Parents provided verbal informed consent after they received verbal and written information about the study. The Institutional Review Board (Comité de Protection des Personnes de l’hôpital de Saint Germain en Laye) approved the study (December 14th, 2000). We screened 12,179 infants with the PREAUT grid at four (PREAUT-4) and/or nine (PREAUT-9) months. Of these, 4,835 toddlers were screened with the CHAT at 24 months (CHAT-24).

Screening tools

PREAUT grid.

The PREAUT grid was developed through observation of family home movies of babies who were later diagnosed with autism and clinical work with at-risk infants [74]. Laznik hypothesized that babies who are at risk of developing ASD may present a deficit of the innate need to interact and be a source of pleasure for the person with whom they interact, in contrast to healthy infants [70]. The PREAUT grid evaluates the infant’s ability to spontaneously engage in synchronous and joyful interactions [72]. The PREAUT grid items (e.g. spontaneously or not looking at the examiner/soliciting his mother) were formulated to reflect the lack of social initiative; the more an infant is actively engaged during an interaction, the higher the score. The grid is scored by a pediatrician during a visit with the infant and its mother (or another care-giver). The doctor observes how the infant behaves, with him and with its mother, not only when it is solicited but also when nobody directly engages it. The grid is provided in S1 Table.

The grid includes an initial group of four items and a second group of six complementary items. The second group of items is only completed if the infant showed at-risk behaviors in response to the first four items (score for the first group of items ≤ 3 at four months or ≤ 5 at nine months). Items are weighted in the grid such that, at four months of age, infants are scored “positive” when they do not spontaneously look at the observer, do not spontaneously elicit the gaze of their mother (or other significant caregiver), and do not try to provoke positive reactions from their mother (or another significant caregiver). At this age, the pathological at-risk threshold was set to ≤ 3 (for a maximum score of 15) based on previous work on West syndrome [72]. In a preliminary exploratory study in the general population, we found that very few infants (one ASD case out of three positive infants) met the pathological threshold at nine months of age with the same threshold. Thus, we decided to move the threshold to ≤ 5 of 15, which appeared to be the best cut-off to define more infants as at-risk without decreasing specificity (with the new threshold, the rate of true positive became four ASD cases out of eleven positive infants). Thus, at nine months of age, infants were scored “positive” when they did not spontaneously elicit the gaze of their caregiver or try to provoke positive reactions from their caregiver, and either did not spontaneously look at the observer/or did not try to be looked at by their mother (vocalizing, intensely gazing, or wriggling) even when she was addressing them. Thus, with this new threshold, the nine-month-old infant was considered to be at-risk if it did not respond to its mother’s attempts to engage it, even if it looked at the observer, whereas the four-month-old infant was considered to be not at-risk, provided that it looked at the observer. We did not calculate interrater reliability in this study. However a previous inter-rater reliability study using the PREAUT grid, with other raters but conducted and supervised by the same team, found Kappa coefficients between 0.74 and 1 for each item [72].

The Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (CHAT).

The CHAT is a screening instrument that identifies children who are at risk for autism by assessing common play habits and behaviors for infants between the ages of 18 and 24 months. Nine questions that evaluate social interest, motor play, pretend play, pointing, and showing are addressed to parents (items A), and five items assess the child’s behavior and reactions to stimuli that are initiated by the examiner (items B: gaze exchange, pretend play, proto-declarative pointing, pointing comprehension, and constructing a tower with blocks) [41, 52, 75]. Infants are considered to be at high risk when they fail all five key items. Infants are “positive”, with a medium risk, if they fail to point (proto-declarative pointing), both as reported by the mother (A7) and observed by the examiner (B4) [37]. We set the threshold to medium risk to increase sensitivity. The CHAT was administered at 24 months of age to coincide with the systematic examination schedule in France.

Procedure

The first step of the study involved training six hundred pediatricians and general practitioners, who worked in the mother/infant protection services (PMI) of the 10 departments, to use the screening tools. Training included a presentation of general information on autism, the study’s goals and methodology, and the study screening tools. Practitioners role-played in small groups to learn how to use the instruments. Video sessions were conducted to illustrate scoring or assess their ability to use the tools.

The second step aimed to screen at least 10,000 infants to obtain sufficient statistical power to account for a drop-out rate of 50% during the two years of screening. The flow of the study is summarized in Fig 1.

Download:

During the first year, we screened 12,179 infants with the PREAUT grid at four and/or nine months, of which 8,933 were screened at both ages. Overall, 3,062 infants were screened with the PREAUT grid at four months only and 183 at nine months only, because of missing data or cancelled visits. Of the 12,179 infants screened with the PREAUT grid, 4,835 toddlers were screened with the CHAT at 24 months, indicating that 7,342 were lost during follow-up before the two-year visit. Two patients were excluded due to premature death and poly-handicaps. There were no significant differences between infants screened with the CHAT and those lost by the 24-month assessment for gender (χ2 = 0.37, p = 0.54) or age at the first PREAUT grid assessment (mean = 3.82 months (SD = 1.69) vs. mean = 3.79 (SD = 1.68), t = -1.17, p = 0.24). However, there was a significant difference in PREAUT grid scores (mean = 14.46 (SD = 2.05) vs. mean = 14.59 (SD = 2.69), t = 3.17, p = .002). There were no differences in the frequency of individuals who screened positive at the first PREAUT grid assessment (1% vs. 0.8%, χ2 = 1.12, p = 0.29).

The third step consisted of (1) the medical diagnosis between three and four years of age for the infants and toddlers who screened positive, using any of the screening tools, and (2) estimating false negatives. All 100 children who screened positive (using either the PREAUT grid at four or nine months, or the CHAT at 24 months) were offered a follow-up appointment. Developmental milestones were systematically assessed during the compulsory visits and included perinatal parameters (pregnancy, childbirth, term birth weight, Apgar) and medical history (for the child and family). Physicians from the PMI center planned physical examinations during the child’s third or fourth year in which a trained psychologist administered the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) and Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence (WPPSI) or Brunet-Lezine test. When appropriate, the psychologist clinically assessed ASD symptoms to establish a positive clinical diagnosis according to the ICD-10 classification. In addition to this follow-up appointment, children who were positive at any step of the screening process were immediately referred to specialized care services which subsequently provided clinical assessment for the final diagnosis. In general, French recommendation for autism made compulsory to use a standardized instrument (e.g. Autism Diagnosis Observation Schedule or Autism Diagnostic Interview) [76]. However, given the sample size, these assessments were not conducted by the research team and rather by specialized care services close to patient’s family home. If the diagnosis of ASD was still questionable, a child psychiatrist from the research team obtained supplementary information from handicap services and the child’s school to better understand the educational arrangements for the child. In total, 45 children (45%) received an estimated diagnosis at the end of the study. Of the 17 children receiving an ASD or ID diagnosis, 15 were followed by specialized services professionals who provided a diagnosis and/or described symptoms consistent with the ASD or ID diagnosis; for the other two cases, the parents refused specialized consultations, but the PMI practitioner and school psychologist (based on behavioral observation and psychometric tests) provided a description of symptoms concordant with ASD (in one case) and ID (in the other case). Finally, all diagnoses were based on clinical symptoms according to CIM-10 diagnosis. As regards complementary testing and assessments, of the 7 ASD cases detected by PREAUT screening, 2 were assessed with gold-standard diagnosis tools in a specialized center, 4 had a broader assessment to explore ASD and ID (CARS, WIPPSI, WISC, MRI, EEG, genetic testing) and 1 received only a clinical CIM-10 diagnosis. For the 6 ASD cases detected by the CHAT at 24 months, 2 were assessed in a specialized center, 3 had broader assessment to explore ASD and ID, 1 had only a clinical diagnosis (see Table B in S2 Table). Six children received an “other” diagnosis (see details in the Results section). Information to support the diagnoses came from specialized services for three, from nursery school examinations for two, and from the school psychologist for the last case. For the 22 children who received no diagnosis (healthy children), most simply had a clinical evaluation (with or without tests) that was supported by school feed-back indicating that the child was developing well. There were no significant differences between those who received an estimated diagnosis and those who were lost to the study based on gender (χ2 = 0.07, p = 0.79), age at first PREAUT grid assessment (mean = 4.14 months (SD = 1.37) vs. mean = 3.95 (SD = 1.02), t = -0.767, p = 0.44), or the percentage of children at risk after CHAT screening (χ2 = 0.50, p = 0.48). However, there was a significant difference in PREAUT grid scores (mean = 8.98 (SD = 6.35) vs. mean = 12.0 (SD = 4.19), t = 2.73, p = 0.008), such that children who were positive by the PREAUT grid screen had better follow-up rates than those who did not screen positive during the first year.

We randomly selected 1,100 children who were negative by all screening instruments to assess their outcomes and identify neurodevelopmental disorders (false negative cases). The physicians from the PMI centers obtained information concerning the children at four to five years of age through systematic reviews that were performed at school or in follow-up appointments. Most had a « nursery school examination » that included general aspects of how they functioned in school and more specific aspects of development, such as gross motor skills, body image, fine motor skills, perceptual organization, language expression, and language comprehension. If the diagnosis was questionable, a child psychiatrist from the research team obtained supplementary information from handicap services. Children were lost for diagnosis when their information was incomplete. A total of 579 children (52.6%) had an estimated diagnosis at the end of the study. Among the 1,100 children who were randomly selected and showed negative results for all screening tools, there were no significant differences between those who received an estimated diagnosis and those who were lost for diagnosis based on gender (χ2 = 0.007, p = 0.93), age at first PREAUT assessment (mean = 3.79 (SD = .99) vs. mean = 3.86 (SD = 1.35), t = .99, p = 0.32), or PREAUT score (mean = 14.55 (SD = 1.83) vs. mean = 14.42 (SD = 2.09), t = -1.11, p = 0.27).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using the statistical package R, version 2.12.2. The α significance level was set to 0.05 and all statistical tests were two-tailed. Qualitative variables were analyzed with chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests and quantitative variables with Student’s t-tests. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated. PPVs were calculated based on the current data and allowed us to answer the following question: « Given a positive test result, what is the new probability of ASD? »

Most studies use theoretical estimations that are based on known ASD prevalence estimates to calculate sensitivity and specificity. Sensitivity often demonstrates the lowest performance and is defined as the ability of a screening tool to correctly identify (true positives) those patients with the disease (ASD). We examined the 1,100 followed-up individuals who were negative for all screenings to calculate sensitivity and specificity. First, we estimated the number of true positives (for the children followed and the children lost after a positive screening) and false negatives in the total sample (in the randomly selected sample of 1,100 children with a preliminary diagnosis and in the children lost to follow-up). We used two approaches using different PPVs. The first estimation was based on the uncorrected PPV for each tool administered to our sample, independently from other screening tests, to determine the prevalence of ASD in children who screened positive, but were lost to follow-up.

The ASD risk for the children who screened positive and were lost to follow-up was overestimated using this uncorrected method, because most were only positive by one screening tool. The risk for the children who were followed who screened positive by several tools was higher than for those who were positive by only one tool. The second estimation used a corrected PPV that accounted for the possibility of scoring positive by only one of several tools. This second estimation used a corrected PPV considering the specific risk of an autistic outcome for infants who were positive by one tool and negative by the others. Thus, the corrected PPV was extrapolated for each lost case from the PPV of the non-lost children with exactly the same combination of screening results: if the lost child was positive at each step, we applied the (higher) PPV of infants with the same screening profile, if the lost child was positive at only one step, we applied the (lower) PPV of infants positive only at the same step.

Recent studies have shown a gender effect interaction with early screening [77]. We thus used a binomial linear mixed model (LMM) to assess whether gender directly or indirectly affected the early screening prediction. We constructed three LMMs to explain the ASD diagnostic status at four years of age. The first included the PREAUT grid screen at four months, gender, and the interaction of the two explicative variables [glm(formula = Diagnosis at follow-up~PREAUT-4+gender+PREAUT-4*gender, family = « binomial », data = data)]. The two other LMMs were similar, one for the PREAUT grid screen at nine months and the other for the CHAT screen at 24 months.

Results

Association between the PREAUT grid and the CHAT (Table 1)

Download:

Overall, 4,835 children (2,385 girls (49%); 2,450 boys (51%)) were assessed with the PREAUT grid at four and/or nine months and the CHAT at 24 months. One hundred infants were positive on at least one screen and six were positive on two or three tests. We examined significant associations between a positive score on the PREAUT grid and each item of the CHAT using the Holm-Bonferroni adjusted p value (due to multiple analyses). At the age of four months, the PREAUT grid (threshold = 3) significantly predicted failure on several CHAT items at 24 months (A5, B2, B3, B4). Additionally, at nine months, the PREAUT grid (threshold = 5) significantly predicted failure on items A7 (protodeclarative pointing) and B2 (following a point) of the CHAT. Of note, A5, A7, B2, B3, and B4 are the five key items of the CHAT. Moreover, a positive score at four or nine months with the PREAUT grid predicted medium- and high-risk status on the CHAT at 24 months with odds ratios ranging from 12.3 to 78.0 (all p < 0.001) (see Table 1).

Positive predictive values

Children who were positive by one of the screening instruments (PREAUT-4, PREAUT-9, or CHAT-24) were systematically evaluated to identify developmental disorders (DD), including ID and ASD. Of the 100 children who screened positive at step one, 45 received a preliminary diagnosis at follow-up; of these, 22 were healthy, 10 were diagnosed with ASD, seven with ID, and six with another DD [specific DD of speech and language (N = 2), multidimensionally impaired (N = 2), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD, N = 1), and mixed disorders of conduct and emotions (N = 1)]. The clinical outcome of positive infants for ASD and/or ID at one (or more) screening point is shown in Table A in S2 Table. Also, detailed clinical characteristics are given in Table B in S2 Table for children who received a diagnosis of ASD and/or ID. They were 4 females and 13 males. Cases show a large heterogeneity. Interestingly all females were positive at early screening and received a diagnosis of ID comorbid or not with ASD including 2 with a causal genetic condition. In terms of timing of screening new patients whom diagnosis was confirmed at follow-up, we had 10 individuals (5 with ASD and 5 with ID) who were positive at 4 months screening, 3 new individuals (2 with ASD and 1 with ID) who were positive at 9 months screening, and 4 additional individuals (3 with ASD and 1 with ID) who were positive at 24 months screening, leading to a total of 17 individuals with ASD or ID.

The estimated PPVs are presented for ASD only and for neurodevelopmental disorders (ASD or ID) in Table 2. Details on the estimations for the total sample of 4,835 individuals are provided in S3 Table for ASD only and S4 Table for ASD and ID. For the PREAUT-4, the mean PPV was 25.9% for ASD and 52.2% for global neurodevelopmental disorders (ID+ASD). For the PREAUT-9, the mean PPV was 28.3% for ASD and 39.2% for ID+ASD. For the CHAT-24, the PPV was 26.6% for ASD and 32.7% for ID+ASD.

Download:

Sensitivity, specificity, and negative predictive value (NPV)

We first calculated the false negative and true positive cases (S3 and S4 Tables) to calculate sensitivity and specificity. We selected 1,100 toddlers who screened negative at random to determine their outcomes and track false negative cases. Of the 1,100 children, five had not received the CHAT and were excluded, and 516 were lost to follow-up (did not attend the PMI assessment, moved, or refused). Of the remaining 579 children, one female was diagnosed with ASD (see Table B in S2 Table). Of the remaining 578 children without ASD, 52 were diagnosed with other disorders based on the pediatrician’s estimate (language delays, global developmental delays, or conduct disorder). From the 4,735 cases that were negative at all screenings (PREAUT-4, PREAUT-9, and CHAT-24), we extrapolated the number of false negatives from the subsample of 1,100 children who were randomly selected for follow-up. From the 579 cases that had all-negative screens and were followed-up, one had an ASD diagnosis (false negative). Thus, we extrapolated eight false negative cases from the 4,735 cases with negative screens.

We calculated the number of true positive cases using two strategies to account (or not) for the likelihood that screening positive on one tool increased the probability of screening positive on another. Of the 45 children who screened positive on the PREAUT or CHAT and were followed-up, 10 were diagnosed with ASD. Fifty-five children who screened positive on one tool were lost to follow-up (N = 3 PREAUT-4+, N = 29 PREAUT-9+, N = 1 PREAUT-9/CHAT-24+, N = 22 CHAT-24+).

We estimated that 18 ASD cases were detected but lost, using the first method, which showed the PPVs for each tool (0.79 at PREAUT-4, 10.92 at PREAUT-9, and 6.28 at CHAT-24, see S3 Table). Thus, the number of ASD diagnoses in our sample of 4,835 toddlers was 36 using this estimation (10 cases that were screened and followed-up, plus 18 true positive cases that were lost to follow-up, plus 8 false negative cases), giving a prevalence of ASD of 0.74% (36/4,835).

The second method provides a lower estimate of true positive cases and accounts for the likelihood that screening positive on more than one tool increases the probability of an ASD diagnosis. We had to simultaneously account for the three screening results to correctly estimate risk. Thus, the risk was lower in our sample of children who were lost to follow-up (with only one child positive on two tools: P9 and C24) than the raw PPV observed in our sample of 45 children who were followed (with many children positive on two or three tools): the PPV of being positive only on the PREAUT-4 decreased from 26.3 to 20.0%, only on the PREAUT-9 from 36.4 to 14.3%, and only on the CHAT-24 from 27.3 to 16.7%. Thus, we estimated that we had nine ASD diagnoses that were detected, but lost (0.60 at PREAUT-4, 4.29 at PREAUT-9, and 3.8 at CHAT-24). The number of ASD diagnoses in our sample of 4,835 toddlers was 27 using this estimation (10 cases screened and followed-up, plus nine true positive cases that were lost to follow-up, plus nine false negative cases), giving a prevalence of ASD of 0.56% (27/4,835).